Mametz Wood - The Royal Welch Fusiliers

By Lt-Gen Jonathon Riley

The following, is an address given by Lt-Gen Jonathon Riley at the Welsh National Commemoration on the Somme

Mae gwaedd y bechgyn lond y gwynt

A’u gwaed yn gymysg efo’r glaw

Their cry is in the wind

Their blood is in the rain

The words of the Welsh bard and shepherd Ellis Humphrey Evans, Hedd Wyn, who joined the 15th Battalion of the Royal Welch Fusiliers in the aftermath of their dreadful baptism of fire in the Somme battles, and who immediately absorbed the atmosphere that this experience had left and the way that it had marked the men who had taken part. It was, too, almost at once a mark in the national consciousness, and so it remains in our collective memory 100 years on.

The Battle 38th (Welsh) Division was one of three Welsh divisions in the army at that time. The 68th Division remained at home. The 53rd Division, made up of Territorial Army soldiers, had already been in action at Gallipoli in 1915. The 38th Welsh Division was a formation raised as part of Kitchener’s New Army in late 1914, and it numbered about 18,500 men; but there was scarcely anyone with military experience, save for the few regular officers and NCOs drafted in to form, train, administer and command the units. The rest were, as Shakespeare puts it, ‘But warriors for the working day’.

The division deployed to France in November 1915 and from January until June 1916 the officers and men took their turn in the drudgery of trenches, learning their trade and being slowly transformed from a bunch of amateurs into something approaching a formation capable of simple tasks.

It had always been envisaged that the New Army formations would not be committed to complex, combined-arms actions until 1917. However the German offensive at Verdun and the need to support Britain’s major ally, France, by attacking the Germans earlier than had been planned on the Western Front, brought forward their committal to the summer of 1916.

The Somme offensive was launched on 1 July, after the most extensive preparations that had then been made in the entire history of the British Army and this should not be forgotten. In many places, as we know, the attack was stopped dead – literally – with horrific casualties. But not everywhere. Around Mametz, gains had been made with few casualties: the 1st Battalion of the Royal Welch Fusiliers, Siegfried Sassoon among them, lost only four men killed and 35 wounded that day while taking all their objectives – not at all the usual story.

To maintain the momentum of the offensive, Haig therefore decided to reinforce this success and attack again around Fricourt in order to capture the German second defence line at its closest point. General Sir Henry Rawlinson, whose Fourth Army was to make the attack, had little option but to assault this position, which was a low but commanding ridge, frontally. He decided to do so between the two large woods of Mametz on the left and Trones on the right. The assault would be phased in order to provide the maximum possible weight of artillery fire in support of the assaulting troops. Mametz would be taken first, to secure the flank against the inevitable German counter-attack. Over the next few days, more progress was made, but the bulk of Mametz Wood remained in German hands. The task of clearing it was now allocated to XIV Corps under Lieutenant-General Sir Henry Horne, who decided to attack the wood from two directions using two divisions: on 7 July, one hundred years ago today, the 17th Division would attack from the West, and 38th (Welsh) Division would attack across open ground from the East. In all, 27 infantry and pioneer battalions, from the four Welsh Regiments, with Welsh artillery, engineer, signals, machine gun and medical units, were committed in this phase of the battle.

Mametz was a mature deciduous wood, about one mile long from north to south and varying in width, with large trees and very thick undergrowth. It was dissected by a series of lateral rides running east to west and one long vertical ride running south to north. The other woods around Mametz were smaller, but equally thick, and all were incorporated into the German defence scheme. Between the woods, the slopes were chiefly open meadows typical of chalk downland. The line of assault would take the troops parallel with the German second line trenches and without suppressing artillery fire and a smoke barrage, the troops would be raked by flanking fire from German strong-points.

The poet and writer Llewelyn Wyn Griffith was a staff officer in the Headquarters of 115 Brigade, which with 113 and 114 Brigades made up the bulk of the division’s fighting strength. The brigade consisted of 17th R.W. Fus, 10th and 11th SWB, 16th and 19th Welch along with supporting arms. The brigade commander, Brigadier-General Horatio Evans, was an experienced old solder; he thought the attack plan was mad – and said so.

Sure enough, the first attack by 17th Division failed but the 38th Division’s assault went in at 08.30 hrs. The attack failed to get within 300 yards of the Wood and in the process more than 400 casualties were taken: we lost as many of our people in those fifteen minutes as we did in fifteen years in Afghanistan. A second attempt was made at 11.00 o’clock with a similar result. A third attempt was ordered for 4.30: it had been raining hard all day, the ground was sodden, the trenches half filled with mud and water, the approach to the Wood was down a slope which had become near-impossible, and all the telephone lines used to call in artillery fire support had been broken. Brigadier-General Evans was convinced that another attack under these conditions would end in disaster. Accordingly, he got the operation called off, thus saving many hundreds of lives – but he knew that it had put an end to his career. It did – and it ended too the career of the divisional commander, Major-General Ivor Phillipps.

After a postponement, 113 and 114 Brigades were ordered to attack the Wood again on 10 July with 115 in reserve using experimental bombing tactics pioneered by the 1st Battalion R.W. Fus and later adopted by the whole Army, supported by three lifts of the artillery barrage within the wood. To everyone’s astonishment, the attack succeeded but once in the Wood, it became a very confused affair, not least because of the dense undergrowth and the destruction caused by the artillery. At one point there were eleven Welsh battalions in the Wood and by dark, the Germans had been pushed back to 300 yards from the northern end.

In his memoir Up to Mametz, Llewelyn Wyn Griffith describes the scene in the Wood: the shattered trees, the bursting shells, the litter of discarded equipment, the mangled corpses of the dead – an experience that stayed with him all his life and came back to him in snatches of nightmare, not least because his younger brother, Watcyn, was killed there and never found, something for which he blamed himself. David Jones’s poem In Parenthesis is also very largely based on these same horrific scenes in the wood. Emlyn Davies, who had joined 17 R.W. Fus with Watcyn, later wrote Taffy Went to War, and said this of the inside of the wood: ‘Gory scenes met our gaze. Mangled corpses in khaki and in field-grey; dismembered bodies, severed heads and limbs; lumps of torn flesh half way up the tree trunks. . . Shells of all calibres burst in plenteous continuance; furies of flying machine gun bullets swept from three directions.’

A final effort on 11 July consolidated most of the Wood and the division was relieved the next day. It was a victory – we should not forget that – but victory at a heavy price. 190 officers and 3,803 N.C.O.s and men of the 38th Division were killed, wounded or missing – casualties were especially heavy among junior officers and sergeants – leading from the front – but five of the infantry battalions lost their commanding officers. It was this level of losses, approaching a quarter of the division’s strength and probably one-third of the combat units, combined with the severity of the conditions, that made such a mark on the art and literature of the battle, so much of it created by Welsh officers and men; and such a mark on the individual and collective memory of the Welsh soldiers, who had endured something which to us is unimaginable – for a band of scorched earth, the war, lies between us and them. It was an experience that created an extraordinary bond between those who had been there – something that could not and cannot be understood by anyone who was not there. Robert Graves entered the wood soon after the 38th Division was relieved and the last words, from his poem Two Fusiliers, which capture this feeling, belong to him:

And have we done with war at last?

Well we’ve been lucky devils, both

And we’ve no need of pledge or oath

to bind our lovely friendship fast.

By firmer stuff

Close bound enough

Show me the two so closely bound

As we, by the wet bond of blood,

By friendship blossoming from mud,

By Death: we faced him, and we found

Beauty in Death,

In dead men, breath.

Memetz News

Visions of World War One, part of World War One BBC Wales

Lt-General Jonathon Riley examines the work of artist and poet, David Jones

July 7 2016

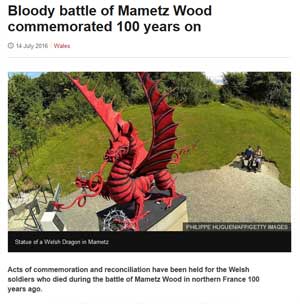

Acts of commemoration and reconciliation have been held for the Welsh soldiers who died during the battle of Mametz Wood in northern France 100 years ago... » (see BBC News article)

July 7 2016

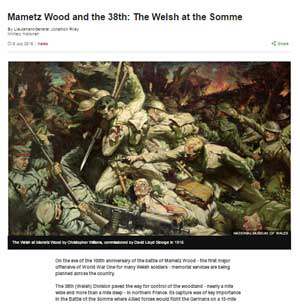

Mametz Wood and the 38th: 'What dark convulsed cacophony' by Lt-Gen Riley

In the first of two written documentaries, Lieutenant-General Jonathon Riley describes the events leading up to and during the battle... » (see BBC News article)

July 6 2016

July 7 2016

Part Two Mametz Wood and the 38th: The Welsh at the Somme by Lt-Gen Riley » (see BBC News article)