Llewellyn Wyn Griffith and The Great War

100 Years On (1914 – 1918)

by Jonathon Riley

Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion January 2014

Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion January 2014

Delivered By Major-General Jonathon Riley DSO

It is fitting that this Society should begin its programme for the centenary year of the outbreak of the Great War by looking at the London Welsh and in it, one of its most distinguished former members. My credentials for submitting this paper, aside from being having commanded the Royal Welch Fusiliers and later been their Colonel, is that I edited the latest edition of Wyn Griffith’s memoir, Up to Mametz, along with its previously unknown sequel, Beyond Mametz. 1

Up To Mametz has long been rightly regarded as one of the classic texts of the Great War. However, when it was first published in 1931 its showing was rather poor, for it sold no more than one thousand copies, in spite of being well reviewed: it is well-written, easy to read and extraordinarily vivid. But it followed the publication of a series of other war memoirs, all of which received great critical acclaim: Edmund Blunden’s Undertones of War in 1928; Robert Graves’s Goodbye to All That in 1929 and Siegfried Sassoon’s Memoirs of an Infantry Officer in 1930. It seems that when he first wrote it, Wyn Griffith wrapped the manuscript in paper and put it away for his children to read in later years. It was only when his friends, the novelist Margaret Storm Jameson 2 and the poet Sir Herbert Read 3 became aware of it, that it was published.

It has since had two successful re-issues and now ranks alongside the works of other Great War writers. Many of the most notable writers, poets, artists and performers of this period also served in the same Regiment as Wyn Griffith, The Royal Welch Fusiliers: Robert Graves, Siegfried Sassoon, David Jones, Frank Richards, J.C. Dunn, Vivian de Sola Pinto and the Welsh-speaking bard Ellis Humphrey Evans, or Hedd Wyn; to whom we may also add Arthur Askey, Bill Tucker, Bernard Adams, Edward Vulliamy and Wynn Powell Wheldon. It is almost easier to list the writers and artists of the war who did not serve in the Royal Welch Fusiliers, rather than those who did.

This remarkable flowering of talent in one regiment was not, however, an isolated episode. There is more written by and about The Royal Welch Fusiliers than any other regiment in the British Army. The intellectual tradition – be it in graphic art, performing, poetry or writing – has long existed in the regiment, sometimes it must be said, co-existing uneasily with a strong sporting and anti-intellectual tendency: in the 1920s, for example, it was said of the officers of the regiment that they thought and talked of nothing but hunting, racing and polo! But this intellectual tradition, which embraces officers and enlisted men as well as wives, can be traced at least to the American Revolutionary War period, with the writings of Roger Lamb, Frederick Mackenzie, Thomas Saumarez and Harry Calvert; into the Napoleonic period with Thomas Henry Browne and his sister, Felica Hemans – who among many poems wrote The Boy Stood on the Burning Deck – Richard Bentinck, Robert Barclay, Richard Roberts, Thomas Edwards-Tucker and Jenny Jones. There were others during the Crimean and later Victorian period whom we have only just begun to uncover. Later, during the Second World War, we can number Desmond Llewellyn, Kyffin Williams, Jack Hawkins, Tony Farrar-Hockley, Bill Ward and Anthony Crosland. Since 1945 our artistic and literary community has included Veronica Bamfield, William Roache, Jon Latimer, Tim Kilvert-Jones, Morgan Llewellyn and Toby Ward.

* * *

Llewellyn Wyn Griffith was born into a Welsh speaking family in Llandrillo yn Rhos in North Wales and he attended Blaenau Ffestiniog County School, where his father John Griffith taught science and music. 4 In 1905, John was appointed headmaster of Dolgellau Grammar School and there the family moved. John remained head until he retired in 1925 after which he was chairman of Harlech festival and editor of the English section of Y Cerddor. John clearly hoped that his son would go to Cambridge but instead, aged 16, he sat and passed the Civil Service Examination. It seems that he sat for a scholarship examination that would have provided funds to help him through his further education, but there were two very strong competitors also sitting for the same scholarship and Wyn Griffith was bested and so instead turned to the Civil Service. His first job was employed in the Liverpool Tax Office of the Inland Revenue as an Assistant Surveyor of Taxes and it was here in Liverpool that he met the girl he later married, Elizabeth Winifred Frimston, also known as Wyn. She was in fact a distant cousin from a St Asaph family – Welsh speaking, although Wyn Griffith noted in his manuscript that the girls of the family “did not speak it from choice”. 5

In 1912, Wyn Griffith was transferred to London, where he embraced the cultural and artistic life with relish, attending the salon of Mrs Ellis Griffith, later Lady Ellis-Griffith, wife of the Liberal MP for Anglesey; 6 and it was at this time that he began writing his first essays. At the same time, his father, who had inherited a modest sum, paid for him to study for the bar at the Middle Temple while continuing his work for the revenue.

Wyn Griffith was 24 at the outbreak of the Great War. On 4 August 1914 he was, like many people, on holiday, enjoying the hot weather of that year. He returned immediately to London to enlist but found to his chagrin that he was in a protected occupation; the rules were, however, soon relaxed and with a friend he tried to enlist in the Royal Naval Division, an infantry division formed from men who could not be employed with the fleet. When his friend failed the medical examination, both turned instead to a Territorial Army battalion, the 7th (Montgomery and Merioneth) Battalion of The Royal Welch Fusiliers at Newtown – where the medical criteria proved less stringent! Shortly before Christmas, he received a letter from his friend Mrs Ellis Griffith telling him of the raising of the 15th Battalion (1st London Welsh) of the Royal Welch Fusiliers. He applied at once for a commission and was accepted in January 1915.

* * *

There were in the pre-war Territorial Army regiments of London Irish and London Scottish – indeed they still exist – but there was no London Welsh. 15 RWF was therefore raised as a war-service battalion, in the Inns of Court, as part of the formation of Kitchener’s New Army – an army for the long war that he was the first to recognise. Battalions like it were being raised all over the country; Wales played its part: in spite of the paucity of population, The Royal Welch Fusiliers raised the fourth highest number of battalions – forty – of all regiments during the war, beaten only by those with large urban population in: Greater London and Middlesex, and the industrial North. David Lloyd George was active in the campaign to expand the army in Wales, espousing even a Welsh Army Corps. This in the end came to nothing, for two main reasons. First, even allowing for the herculean effort of raising the numbers of troops that it did, Wales could not support a corps of perhaps 40,000 men for several years – especially as the high command of the army would not extract the regular Welsh infantry and Cavalry units from their parent formations to provide the backbone of a new corps. Secondly, Welsh Army Corps would have opened the door for similar formations in Scotland and Ireland. An army corps can be a powerful instrument in the formation of new nations, as those of Australia, New Zealand and Canada showed and at this time, just before the war, the issue of the moment had been Irish home rule. This had been shelved for the duration and no-one in London would support any move that would keep this issue alive while the bigger matter of war with Germany demanded their full attention. An irish army corps would have done just that at a time when it was important to focus loyalty on the British Army. Wales’s contribution to the war was therefore its regular regiments and its two national divisions, the 38th and the 53rd which served in Europe and the Middle East respectively.

15 RWF was inaugurated at a meeting of London Welshmen on 16 September 1914, presided over by Sir Vincent Evans. 7 It was officially recognised on 29 October and for its first few months, drilled in the garden and square of Gray’s Inn: it was here, after the war, that its memorial was placed and here it still remains. The new battalion left London for Llandudno on 15 December under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel William Fox-Pitt of the Grenadier Guards where it joined 113 (Royal Welch) Infantry Brigade in the 38th Welsh Division. It was here that Wyn Griffith joined them. The next eight months were spent in training in North Wales, at Winchester and on Salisbury Plain.

15 RWF and its home-service partner battalion, the 18th (2nd London Welsh) began by enlisting Welshmen living in London, many of whom were second or third generation exiles – it was said, for example, that one scarcely met a dairyman in London who was not a Carmarthenshire Welshman. Wyn Griffith noted in a recording he made on reported speech that most sounded more cockney than Welsh – but they all felt the pull of their homeland. However this was a limited pool of manpower and before long, the battalions were being made up with drafts from all over Wales.

Returning briefly to the intellectual tradition, the 15th contained several extraordinary people. In addition to Wyn Griffith, there was David Jones, whose iconic (but difficult) work In Parenthesis is based on his experiences with 15 RWF. Then there was Bill Tucker, whose book The Lousier War is one of the few accounts we have of life as a P.O.W. in Germany during the Great War; Tucker later worked for many years on The Times and helped launch The Times Atlas of the World. Thirdly there was Harold Gladstone Lewis, who wrote Crow on a Barbed Wire Fence. Last, the Welsh shepherd and bard from Trawsfynydd, Hedd Wyn, who was killed on Pilckem Ridge in 1917. He won the bardic chair at the National Eisteddfod at Birkenhead in that year and when called to take his place, it was announced that he was dead. The Chair was left empty and draped in black.

There is, however, no mention in any of their works that, at the time, these men were at all aware of each other in the way that in the regular battalions, Graves, Sassoon, Adams, Dunn and Vulliamy, for example, knew each other. Jones, Tucker and Evans were all privates and it is unusual for private soldiers to know anyone outside their own company in wartime – and Evans would also have been separated from the others by language, which can be both a bond and a barrier.

* * *

113 Brigade was one of the three brigades, each of four or five battalions, that made up the fighting strength of the 38th Welsh Division which, including its combat support and administrative units stood at about 18,500 men. However there was scarcely anyone with military experience, save for the few regular officers and N.C.O.’s drafted in to form and train the units. Regular and Special reservists had all been recalled to regular divisions and the Territorial Army had its own divisions – of which the 53rd Welsh was one. Officers in the Service divisions, like 38th, were selected therefore not on any basis of military efficiency but on the basis of patronage – often in the gift of Lloyd George himself. In 15 RWF, Noel Evans, 8 for example, came from a noted Merionethshire family. He was later Deputy Director of Public Prosecutions, a J.P., High Sherriff and Deputy Lord Lieutenant of the County; Goronwy Owen 9 was related to Lloyd-George by marriage. He had a very good war, ending as a Lieutenant-Colonel with a D.S.O. and was later Liberal MP for Caernarvonshire and President of British Controlled Oilfields.

After its months of training – which seems to have consisted mostly of drill, route marches, some rudimentary tactical training and weapon training – the 38th Division was in late November 1915 reviewed by Queen Mary Two days later, 15 RWF received a new Commanding Officer, Lieutenant-Colonel R.C. Bell of the Central India Horse. 10 The brigade also received a new commander, Brigadier-General Llewellyn Alberic Emilius Price-Davies, whom Wyn Griffith describes as the second most stupid soldier he ever met. Price-Davies had done well in the small wars which preceded 1914 and had won a V.C. and a D.S.O. in South Africa. He was, says Griffith, too dull to be frightened. His recently published letters reveal a more complex character than appeared on the surface. 11 Known as “Mary” by his fellow regulars – Wyn Griffith (wrongly) says “Jane”) he exemplified the thoughtless brutality that is many people’s stereotype of the Great War general officer: unimaginative, slow, fascinated by the minor trivia of latrine buckets and polished brass he was one of those who had to be promoted to fill command appointments in a rapidly expanding army, promoted on the basis that bravery in combat signifies the ability to exercise high command – but for whom the demands of modern war were all too much. 12 Under Price-Davies, the brigade embarked for service in France on 1 December 1915 in pouring rain and it is here that Up to Mametz begins in earnest.

From January until June 1916 the 15th Battalion took its turn at the drudgery of trenches, learning its trade and being slowly transformed from amateurs into something approaching a unit capable of simple tasks. Initially they were placed under the mentorship of regular units and even carried out some limited offensive tasks, such as raiding, in which the first casualties were taken.

In the spring of 1916, Wyn Griffith, a temporary captain, took command of C Company in various tours of trenches around Merville and Givenchy and even managed a short spell of home leave. These tours of trenches were not, as many people think, affairs lasting months. In the desperate days of late 1914 and early 1915 there were recorded instances of units holding the line for weeks at a time but by the spring of 1915, most divisions operated a rotation in which each brigade spent a few days in the front line; then a few days in the support line, then days in reserve – these were often the worst period as the men would spend all night on duties like carrying supplies up to the line, or sand-bagging and wiring and other heavy work. This would be followed by a rest period and training, before the rotation began again. In spite of all this, the 38th Division was by no means capable of taking part in a major combined-arms operation against fortified German positions – which was the task they would be given at Mametz.

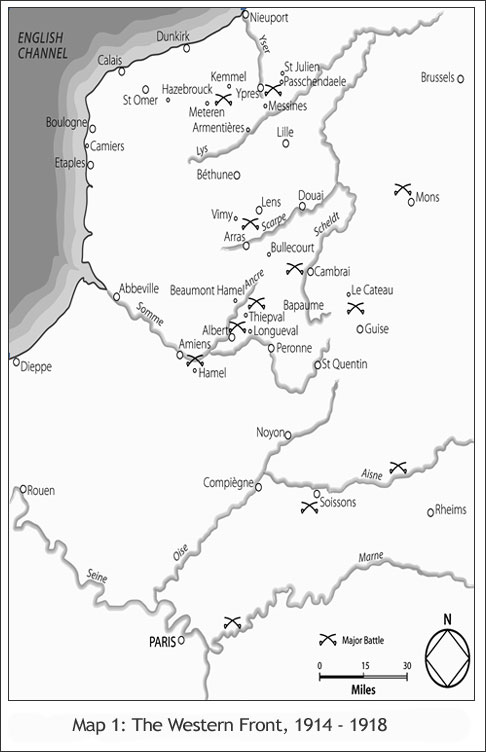

And so we come to the summer of 1916. Allied war strategy for the year had been formulated during a major conference at Chantilly, where it was agreed that major, simultaneous offensives would be launched by the Russians, the Italians in the Alps, and the British and French in the West, thus assailing the Central Powers around the whole perimeter of the war. Shortly after the conference, General Sir Douglas Haig replaced Sir John French as Commander-in-Chief of the British Expeditionary Force. Haig favoured an attack in Flanders, which was easily served by the line of communication through the Channel Ports and which, if it went well, might even drive the Germans away from the Belgian coast from where their submarines were decimating British shipping. However, rather as we are now with the Americans, the British were the junior partners in the coalition with the French and in February 1916, General Joseph Joffre, the French C-in-C, insisted on a joint British and French attack astride the River Somme in Picardy, beginning in August. However, shortly afterwards the Germans launched their attack around Verdun. The French threw all they had into preventing a German breakthrough here, which if it succeeded would open a major avenue of advance towards Paris. Their commitment to the Somme battle was thus significantly reduced and the bulk of the burden shifted to the British and Imperial troops: twenty divisions were now committed as against only thirteen French divisions. Moreover as the mincing machine of Verdun developed, the aim of the Somme offensive changed from being part of a decisive allied blow against Germany, to one of relieving the pressure on the French; the date of the attack was brought forward from August to July. 13

Among senior British commanders there was disagreement on how the required effect would be achieved. General Sir Henry Rawlinson, whose Fourth Army would conduct the attack, favoured a “bite-and-hold” approach, which would concentrate resources and which recognised the British inability to exploit a breakthrough even if one were made. Haig’s concept, by contrast, was for a more general attack on a wider front. Much emphasis was based on the ability of allied artillery to destroy German wire and fortifications and allow the infantry to break in, and then break through. In reality, British field artillery was still woefully behind that of the Germans. Most of it was of light or medium calibres – without therefore the weight of shell needed; it would be another year before the balance of British artillery shifted to medium and heavy calibres and two years before British gunnery was better than that of the enemy – nor had the huge strides in fuse technology that appeared in late 1917 yet emerged, which would allow artillery to cut wire effectively. Finally, without radio, artillery was still controlled on pre-arranged timings. This meant that the infantry had to keep up with the artillery fire as it shifted, rather than the artillery being manoeuvred to support the infantry. If the infantry were held up, the barrage would move on, leaving them exposed. Air support too was in its infancy and could do little other than deliver machine gun fire, or direct artillery by observing the fall of shot and dropping correction messages tied to weights.

Rawlinson was, too, well aware of the quality of the infantry with which he had to make this assault. The first BEF, based on the regular army heavily augmented by reservists, had been effectively wiped out by the battles of 1914; the Territorial Force, which entered the war in 1915, had also been badly depleted. The bulk of the BEF was now therefore made up of the volunteers who had joined Kitchener’s New Army. Kitchener had formed this army with the intention of having it ready for major operations in 1917: yet now, strategic considerations over-ruled their lack of expertise and these units and formations were to be required to undertake a difficult operation, without enough experience, a year earlier than had been intended, and without the compensation of effective fire support.

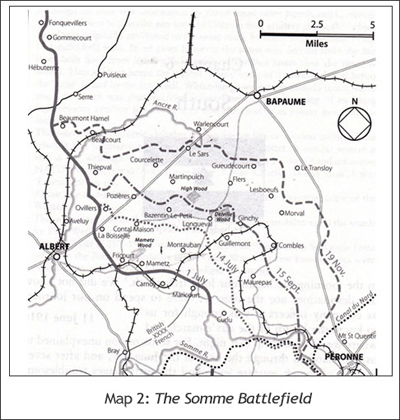

With the benefit of hindsight it is not surprising that except for the area around Montaubin, the objectives of 1 July 1916 were not gained. Here, the 7th and 21st Divisions broke into the German lines around Fricourt and captured Mametz village, shown here. But as so often until 1918, they broke in, but could not break through because of the way that the Germans organised their defence in depth. That evening, Haig decided to reinforce success and attack again around Fricourt in order to capture the German second defence line at its closest point between Longeval and Bazentin. Rawlinson had little option but to attack this position, which was a low but commanding ridge, frontally. He decided to do so between the two large woods of Mametz on the left and Trones on the right. The assault would be phased in order to provide the maximum possible weight of artillery fire in support of the assaulting troops. Mametz would be taken first, in order to secure the flank against the inevitable German counter-attack.

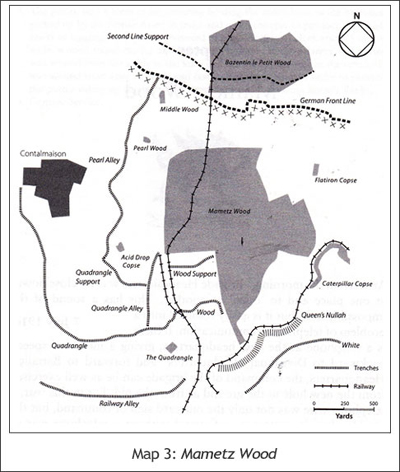

Mametz Wood was allocated to XIV Corps under Lieutenant-General Sir Henry Horne. Horne decided to attack the wood from two directions: 17th Division would attack from the West, out of Quadrangle trench, while 38th Welsh attacked across open ground from the east out of Caterpillar and Marlborough Woods. 38th Division was to attack in echelon, that is, with the first assault brigade, 115, leading, followed by the second brigade, followed by the third. The line of assault would take the troops parallel with the German second line trenches and without suppressing artillery fire and a smoke barrage, the troops would be raked by flanking fire from German strong-points in Sabot and Flat Iron copses.

Not long before the start of the Somme battle, Wyn Griffith had been posted as a staff learner to Headquarters 115 Brigade, which consisted of 17th RWF, 10th and 11th SWB, 16th and 19th Welch along with a field artillery brigade, machine-gun company, trench mortar battery and a field ambulance company. The brigade commander, Brigadier-General Horatio Evans, 14 was an old soldier not at all in the mould of Price-Davies. As Wyn Griffith recalled, Evans thought the plan was mad. Not surprisingly, the attack failed to get within 300 yards of the Wood, not least because the supporting artillery fire did not arrive. Wyn Griffith was at this point with Evans, taking down messages and sending them back or forward as required by runners and field telephone

Not long before the start of the Somme battle, Wyn Griffith had been posted as a staff learner to Headquarters 115 Brigade, which consisted of 17th RWF, 10th and 11th SWB, 16th and 19th Welch along with a field artillery brigade, machine-gun company, trench mortar battery and a field ambulance company. The brigade commander, Brigadier-General Horatio Evans, 14 was an old soldier not at all in the mould of Price-Davies. As Wyn Griffith recalled, Evans thought the plan was mad. Not surprisingly, the attack failed to get within 300 yards of the Wood, not least because the supporting artillery fire did not arrive. Wyn Griffith was at this point with Evans, taking down messages and sending them back or forward as required by runners and field telephone

A second attempt was ordered, but Evans was convinced this would end in disaster. He had tried to get through to the divisional commander, Major-General Ivor Phillips, without success, but Wyn Griffith, who had been speaking to an artillery officer, took him to a captured German dugout, where a heavy artillery brigade had established a forward command post. Here, he spoke to the divisional headquarters and after some argument, got the operation called off, thus saving many hundreds of lives – but he knew that it had put an end to his career. He was in fact posted to a home appointment directly after the battle – found wanting in the offensive spirit by the high command, no doubt.

The next afternoon, 113 and 114 Brigades, including 15th RWF, were ordered to attack the Wood again with 115 in reserve; this attack was postponed until dawn on 10 July and to everyone’s astonishment, it succeeded. In the afternoon, 115 Brigade was ordered to relieve the two assault brigades and take over the defence of the wood against German counter-attacks. Wyn Griffith recorded that Evans and the Brigade Major, C.L. Veal, went up to the Wood and that he followed slightly later: the photograph attached to this paper is catalogued only as a brigadier general and staff in Mametz Wood, but comparing what detail I can with other likenesses, I believe this is a chance photograph of Evans, Wyn Griffith and a runner at exactly this moment. Soon afterwards, Veal was wounded and Wyn Griffith found himself as acting Brigade Major.

In Chapter 7 of Up To Mametz, Wyn Griffith describes the scene in the Wood in some detail: the shattered trees, the bursting shells, the litter of discarded equipment, the mangled corpses of the dead – an experience that stayed with him all his life and came back to him in snatches of nightmare. Word came through by field telephone that 115 Brigade was to complete the clearance of the Wood as soon as possible. Evans decided to make a surprise attack, without a preliminary barrage – but before he could put this plan into operation, the brigade came under fire from British artillery falling short of the German trenches. This fire not only pinned down the brigade, but put a stop to any prospect of a surprise attack for the Germans were now thoroughly roused.

The brigade signals officer, Emlyn Davies 15(whom Wyn Griffith calls “Taylor”), had sent relays of runners back to get the artillery fire shifted. One of these runners was Wyn Griffith’s younger brother, Watcyn. Watcyn got through with his message, but on the way back he was hit by a shell and killed at once. Wyn Griffith learned of Watcyn’s death within an hour – and clearly blamed himself. As brigade major, he had ordered the signals officer to get a message through and therefore, in his own words “I had sent him to his death, bearing a message from my own hand, in an endeavour to save other men’s brothers.” Watcyn’s body was never found and he is one of those therefore, whose grave is unknown.

Stunned as he was, Wyn Griffith still had his duty to attend to, but this sense of guilt clearly remained with him for ever afterwards, mixed with the dreadful memories of the Wood. A set-piece attack next morning completed the clearance of the Wood, after which the 38th Division was relieved in the line and pulled back into rest. Robert Graves was with the 1st Battalion of the Royal Welch Fusiliers when they entered Mametz Wood shortly afterwards and he described the scene thus in Goodbye to All That:

Mametz Wood was full of the dead of the Prussian Guards reserve, big men, and the Royal Welch and South Wales Borderers of the new-army battalions, little men. There was not a single tree unbroken . . . There had been bayonet fighting in the wood. There was a man oif the South Wales Borderers and one of the Lehr Regiment who had succeeded in bayoneting each other simultaneously. A survivor of the fighting told me later that he had seen a young solder if the 14th Royal Welch bayoneting a German in parade-ground style, automatically exclaiming as he had been taught: “in, out, on guard. . . 16

The 38th Division, much reduced in size by casualties, was moved away into rest and this is where Up To Mametz ends. But Wyn Griffith continued to serve in the Army for the rest of the war and it was by chance that I came upon his account of his subsequent service, searching the Royal Welch Fusiliers archive for something quite else. What I found was a short hand-written narrative for family consumption, which picks up where Up To Mametz left off and continues to the end of the war. Some of it found its way into other published works, such as Wyn Griffith’s essay “The Pattern of One Man’s Remembering” in Promise of Greatness. But the manuscript was very short, even when supplemented by another manuscript in which Wyn Griffith described his return to civilian life. I had therefore to annotate it heavily in order to explain the context of events. Even having done that, it had a very incomplete feel to it. I therefore decided, with the family’s consent and assistance, to use Wyn Griffith’s surviving letters and diaries, and some material from his close contemporaries, to ghost-write a sequel, which I called Beyond Mametz. Even this was not easy, for although we know that he wrote every day to Wyn, there was no trace of these letters and I relied on his diaries lodged in the National Library of Wales and on the War Diaries of the various headquarters to which he belonged and which he would have contributed. In doing this I am certain that I was fulfilling his own intentions, for he says in the first chapter of the manuscript that this is the makings of: “. . . the book I had inside me, a book that might have been of some value: the war and the regular soldier and the staff as seen through the eyes of a temporary soldier . . .”

Up To Mametz is one of the iconic accounts of men in combat during the titanic struggles on the Western Front; and it is riven through with feelings of guilt. Guilt about Watcyn, guilt that he, Wyn Griffith, survived where so many others did not. Beyond Mametz is different: it provides a record of the life of an officer on the staff – a species which came in for a good deal of adverse criticism both during and after the war from front line officers: “. . . a bloody nuisance, inefficient where it isn’t actually crooked” as John Masters reported the common view; or more specifically

The function of the staff is so to foul up operations, by giving contradictory orders and misreading their maps, that wars will be prolonged to a point where every staff officer has become a general. 17

The book however begins with the 38th Division moving into a quiet area near Arras, and then to the Ypres salient. For a while, Wyn Griffith remained on the staff of 115 Brigade, under a new commander, Brigadier General Carlos Joseph Hickie; 18 and two new staff officers, Major Arthur Derry 19 and Captain Jim Davies, both of whom Wyn Griffith liked and admired. Then, out of the blue, he was sent as a staff learner to the headquarters of a much larger formation, VIII Corps. Here he met the man he described as the stupidest soldier he ever met – none other than the corps commander, Aylmer Hunter-Weston who had commanded the corps at Gallipoli and remained in command throughout the war. 20 Hunter-Weston was clearly despised by the chief of staff, the able General Leonard Ellington 21 who was in later years Chief of the Air Staff, and laughed at by all the more junior staff officers. He was, like Price-Davies, a buffoon, who displayed all the bad qualities of Great War Generalship and none of the good.

Then, in April 1917, Wyn Greiffith was sent back to his old battalion in the Ypres salient. It was, he admits, “a great shock, and the end of my hopes for promotion.” But he again took over C Company which was holding a section of the line in the Yser Canal sector. Here, only the width of the canal separated the two front lines and the whole area was heavily fortified. The life of an infantry battalion in the line here was minutely described by Wynn Wheldon – a recipient of this society’s medal who was then commanding 14 RWF in the same brigade, in an article in The Welsh Outlook in 1919. Wyn Griffith was of course back under the command of Brigadier-General Price-Davies, whom Wyn Griffith described as “a daily plague to his brigade”; however he found the battalion commanded by a very able officer: Compton Cardew Norman, known as “Crump”, an experienced regimental officer, several times wounded, who brought 15 RWF to its highest level of efficiency. 22 He was gruff and reserved, but kindly – Wyn Griffith said of him that “there was an underlying sympathy with a young man bearing a heavy burden of responsibility, though it was well-concealed on a morning parade when we were out of the line.”

Both Wyn Griffith and Wynn Wheldon say that “Welsh was spoken everywhere”, but this may be a misleading impression. While there was undoubtedly a good deal of Welsh spoken in the trenches and the bonding value of this shared culture must have been immense, Wyn Griffith is seeing things, after the lapse of forty years, through somewhat rose-tinted spectacles. It is not possible to determine the nationality of all those who served in The Royal Welch Fusiliers during the War, because of the destruction by German bombing during the Second World War of the personal files of many (not all) of those who had served in the Great War. However, most entries in the records Officers Died in the Great War and Soldiers Died in the Great War, give the place of birth. From this, it is possible to obtain a good indication of the Welshness of the Regiment. During the War, the Regiment raised forty battalions, of which twenty-two served abroad. Of these, fifteen sustained over 200 casualties. In these fifteen battalions, an average of 47% gave Wales or Monmouthshire as their place of birth. The figure was highest in the Territorial battalions at around 60%, and generally lowest in the regular battalions which had, in peacetime, recruited strongly in London and Birmingham. The service battalions in 38th (Welsh) Division averaged just over 40%: in Wyn Griffith’s own battalion, the London Welsh, this figure is a mere 27%. The idea that the Regiment spoke only Welsh during the war is therefore not sound, and in danger of creating yet another myth of the Great War. Nor does it do service to the many patriotic men who gave their lives, and who spoke no Welsh, but considered themselves no less Welsh for it. 23

This interlude with 15 RWF was short, however, for in June Wyn Griffith was told to report to the headquarters of II ANZAC Corps, later renamed XXII Corps when all Australian units were grouped into a single corps and the New Zealanders sent elsewhere. Wyn Griffith remained on the staff of this corps for the rest of the war. Throughout 1917 and early 1918 they were in the Ypres salient where the first major event was the Third Battle of Ypres in which the corps played a major and highly successful part, capturing the eastern part of Messines Ridge; in 1918 came the great German offensive of March 1918 – on which Wyn Griffith is curiously silent although he never seems to have doubted that the Germans would be stopped, even when things looked grim and all the gains made around Ypres were reversed. Then the corps was moved south rapidly to reinforce the French in Champagne. The corps then returned north to take part in the great advance of the Hundred Days, which ended with the liberation of Valenciennes – a period when the British Army bore the brunt of the war on the Western Front, when it was probably the most complete and capable it has ever been, and when it was the best combined-arms battlefield force in the world, more than a match even for the mighty German Army.

Wyn Griffith’s account of the war in Beyond Mametz provides glimpses of a number of distinguished senior officers, and sketches of many people who achieved distinction in later years; He was able to see how good generalship was exercised, as well as bad, and in particular by the commander of XXII corps, General Sir Alexander Godley. 24 Wyn Griffith painted one particularly vivid picture of Godley fighting the battle around Ypres from a forward dugout, using maps, field telephones and runners; the picture attached to this paper is, I think, him doing just this. This sense of how command was exercised at division and corps level at a time is very valuable, for almost all the ingredients of modern war were present except one: battlefield radio. Commanders of the time, and their staffs, were often criticised for what J.F.C. Fuller described as “château generalship” 25 – that is, for stationing themselves well behind the line and not sharing in the sufferings of the troops. In the 1930s and 1940s, the image of Generals was somewhat tarnished by this sort of mythology: there was a widespread feeling in the Army that at the higher levels of command during the war, a General, having made a plan and issued the orders, then frequently took no part in superintending the implementation or adapting it to changing circumstances: he merely waited in isolation for news. This coloured the views of many of the next generation of senior commanders, and accounts for much of their behaviour during the Second World War. Slim, Montgomery, O’Connor, Horrocks and others were always at pains to be seen in the front line. This sort of thing prompted commentators analysing the lessons of the Great War to remark on the necessity of leadership by example at all levels: this, for instance, from a veteran of Gallipoli: “War with impersonal leadership is a brutal, soul-destroying business . . . Our senior officers must get back to sharing danger and sacrifice with the men, however elevated their rank. . . .” 26

This is unfair on two counts. First, as a British General, you were far more likely to be killed in action during the Great War than during the Second World War, or at any time subsequently. Sixty-one British Generals were killed in action between 1914 and 1918, another nine died of wounds. This includes Brigadier-Generals, and among the Major-Generals were ten divisional commanders. 27 Compare this with only five between 1939 and 1945; 28 four others died in accidents and six more in aircraft crashes.

This in spite of the obvious reaction to the charge of château generalship, that made it such a point of honour for Second World War Generals to be seen leading from the front. The second count bears directly on this. In order to exercise command, a General had to be able to do three essential things: to find out what was going on; to communicate his intentions to his subordinates; and to communicate with the staff so that it could solve problems and implement decisions. In the absence of battlefield radio, the means of doing these three things were personal observation, telephone, telegraph, and runner. The first always had value, but in a dispersed or extended battlefield it might be difficult to do, and might leave the General disconnected from his command for long periods. The others all indicate that the most complete information on which to base decisions would have been at the main headquarters. The simple truth is, therefore, that in those days, the closer a General approached to the front line, the less he could command. This argues for personal reconnaissance and visiting outside the periods of heavy fighting, and for remaining at the centre of communications when battle is joined.

Wyn Griffith was an outsider in the military system, with no axe to grind; indeed he could be brutally frank when he chose. But in general his account – the account of one who had been a regimental officer on the Western Front – is sympathetic to the staff, and to many Generals – but not all. Wyn Griffith had the misfortune to serve under two particularly stupid Generals as well as several good ones. But even the bad ones were not château generals; arguably they spent too much time in the front line. This underlines, therefore, why Wyn Griffith’s account should not be dismissed because it is sympathetic, even though that may go against much of the mythology of the Great War, of the “lions led by donkeys” school of thought which the likes of Hunter Weston and Price-Davies exemplify. This school of thought, which tends to classify every general and staff officer of the Great War in the donkey category clings on, despite the more objective analysis of command on the Western Front begun by John Terraine’s brave collection of essays in 1964, 29 and carried on by others like John Bourne, Gary Sheffield, Richard Holmes and Hew Strachan. Moreover it should not be discounted because it is personal, and because it is contemporary. By using his narrative, and fleshing it out with his letters and diaries as he himself considered doing, but did not complete, it may, in Wyn Griffith’s own words, “[do] . . . full justice to a much-maligned profession, and especially to commands or staff that were the target for all the many published war books.”

While Wyn Griffith was serving on the staff, what became of the London Welsh? In 1917 the battalion took part in the attack on Pilckem Ridge on 30 July during the Third Battle of Ypres. 30 In spite of heavy casualties, especially among the officers, the battalion achieved its objective on Iron Cross Ridge and repelled a heavy German counter-attack before being relieved on 6 August. Among the casualties were Crump Norman, who was wounded, and as we know, Ellis Evans who was killed. The Prince of Wales visited the battalion soon afterwards to congratulate them on their achievements. The battalion then went down to Armentières.

In early 1918, a disagreement developed between Haig and the government at home over the conduct of operations in the forthcoming months. The upshot was that the government withheld further reinforcements from the field army, even though there was no shortage of men, there being around a million trained soldiers in Britain at the time, and about the same in other theatres of war. But the government was fearful of another year of casualties on the scale of 1916 and 1917, should Haig go on the offensive. To maintain the B.E.F. at its full fighting strength of sixty divisions – nearly two million men – at steady state (i.e. during periods outside major phases of operations), required a turnover of almost 10,000 men every month – the equivalent of one division – to replace those killed, wounded, sick, missing, deserted or absent, prisoners and discharges for various reasons. Many of these reinforcements were soldiers recovered from wounds; the balance, by 1918, was made up from conscription in England, Scotland and Wales and by volunteers from Ireland and the Empire. Withholding this level of reinforcement meant that field units and formations would rapidly become too small to hold their allocated frontages of the line. Accordingly, Haig ordered that one battalion in each brigade would be disbanded and the men distributed to keep the rest effective. This reduction of brigades from four to three fighting units was one of the contributory factors in the German success in breaking through the British line in March 1918.

In 115 Brigade, the battalion selected was the London Welsh and it left the line on 14 January 1918. After the war, the battalion was, in common with all the other war-service battalions, presented with a King’s Colour – which we still hold. The battalion’s Association continued for many years; its members held a great celebration on the 50th anniversary commemoration of its raising in 1964. Now, as we approach the centenary, they are of course all gone.

And what of Wyn Griffith? He remained with XXII Corps until he was demobilised in February 1919 and he returned to civilian life with an O.B.E., the French Croix de Guerre and three mentions in despatches. Having survived the war unwounded, he almost died of Spanish flu and it was only Wyn’s devoted nursing that saved him. 31

He returned to the Inland Revenue and moved to London, although home was always the village of Rhiw in North Wales, and helped to launch the Pay-As-You-Earn (P.A.Y.E.) system of income tax. He retired as an Assistant Secretary in 1952. He was Vice Chairman of the Arts Council, Editor of the Proceedings of this society, and a frequent broadcaster – most notably at the Welsh end of the B.B.C. Quiz Around Britain, and as the author of the script for the B.B.C’s V.E. Day coverage in 1945. He was made an Honorary D.Litt by the University of Wales and was made C.B.E. in 1961. He died in 1977, having seen of course another war in which one of his two sons, John, was killed on active service in the RAF in 1942. 32 His and Wyn’s last years were spent in Cheshire. Winifred always said to her children and grandchildren, “mark my words, I shall live longer than your grandfather”. When he died, she lived just three days more – she had no longer any reason to live. They were buried together in the same grave in their beloved village of Rhiw.

REFERENCES

- Llewellyn Wyn Griffith (ed Jonathon Riley) Up to Mametz…and Beyond (Barnsley, 2010).

- Margaret Storm Jameson (1891 – 1986) wrote forty-five novels including three volumes of autobiography. She was a champion of pacifism and anti-fascism.

- Sir Herbert Read DSO MC (1893 – 1968) was an anarchist poet and critic of art and literature. He served on the Western Front in the Green Howards; his second volume of poetry, Naked Warriors, published in 1919, drew on his experiences in the trenches.

- John Griffith (1863 – 1933), musician, scientist and teacher, was born in Rhiw, Lleyn, and educated at Botwnnog Grammar School and Normal College, Bangor. He was appointed teacher at Glanwydden in 1884 and in 1894 moved to Machynlleth. He returned to study at Bangor University and in 1900 took up a science teaching post in Blaenau Ffestiniog. He died at Bangor in 1933.

- Elizabeth Winifred Frimston (1890 – 1977). Her lack of Welsh explains why Wyn Griffith’s letters are in English, not Welsh; however it is likely that the wartime censor would have required them to be written in English.

- Sir Ellis Jones Ellis-Griffith, 1st Baronet PC KC (1860 –1926), was a barrister and Liberal politician. He was born Ellis Jones Griffith, the son of a builder in Blaenau Ffestiniog.

- Sir Evan Vincent Evans (1851-1934) was a prominent member of Welsh cultural organisations and was secretary of the Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion and the National Eisteddfod Society, Chairman of the Royal Commission on Ancient Monuments in Wales and Monmouthshire, and a member of the Royal Commission on the Public Records, as well as being on numerous educational councils; he wrote numerous articles for Welsh newspapers and was involved with several organisations formed for the benefit of Welsh soldiers during the Great War.

- Lewis Noel Vincent Evans CB CBE (1886 – 1967).

- Goronwy Owen (1881 – 1963) had been a founder member of the battalion in 1914.

- Richard Carmichael Bell DSO (1868 - ?) had been commissioned into the South Staffords in 1887 and served with the CIH from 1891 until like many experienced Indian Army officers he volunteered to serve with the New Armies.

- Ed. Peter Robinson, The Letters of Major-General Price-Davies VC CB CMG DSO. From Captain to Major-General (Stroud, 2013).

- Later a Major General, Price-Davies (1875 – 1965) had been commissioned into the K.R.R.C. and won his V.C. at Blood River in September 1901. He was the brother-in-law of Lieutenant-General (later Field Marshal) Sir Henry Wilson who was at this time commanding IV Corps.

- For a full examination of the battle, see, for example, Gary Sheffield The Somme: Forgotten Victory (London, 2001).

- Horatio John Evans (1862 - ?).

- H. Emlyn Davies had joined 17th RWF on the same day and in the same village as Wyn Griffith’s brother, Watcyn. He later wrote Taffy Went to War (Knutsford, 1976).

- Robert Graves, Goodbye to All That (London, 1929), p 253.

- John Masters, The Road Past Mandalay (Watford, 1961) p 199

- Brigadier-General Carlos Joseph Hickie CMG (1873 – 1959) was commissioned into the Glosters in 1893, transferred to the K.O.Y.L.I. in 1902, and again to the Royal Fusiliers in 1912. In 1914 he was Brigade Major of the East Lancashire Infantry Brigade (T.F.). He was appointed to command 115 Infantry Brigade in August 1916 and according to Wyn Griffith’s diary he arrived on 30 August. He also commanded 224 and 7 Infantry Brigades.

- According to the 38th Division History Major Arthur Derry DSO arrived in July, 1916. Wyn Griffith’s diary confirms this, giving the date as 18 July. In 1914, Derry had been D.A.A. & Q.M.G. of the Welsh Division (T.F.) He was still a Major at the end of the war.

- Lieutenant-General Sir Aylmer Gould Hunter-Weston KCB DSO GStJ (1864 – 1940) was commissioned into the Royal Engineers in 1884 and served in Waziristan, Dongola, and South Africa. He commanded VIII Corps in the Dardanelles and on the western Front form 1915 to 1918. He retired in 1919. He was Unionist M.P. for Buteshire and North Ayreshire 1916 – 1935. He died as a result of a mysterious fall from a turret at his family house.

- Later Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir Leonard Ellington GCB CMG CBE (1877 – 1967). He was Chief of the Air Staff 1933 – 1937, and Inspector General of the RAF 1937 – 1940.

- Lieutenant-Colonel (later Brigadier) Compton Cardew Norman CBE CMG DSO (1877 – 1955). A regular officer, he had served in South Africa and with the Royal West African Frontier Force. He was wounded three times during the war, and commanded no less than four battalions. He later commanded 2 R.W.F. 1920 – 1924, 158 (Royal Welch) Infantry Brigade 1927 – 1929, and was Inspector General of the R.W.A.F.F. and the K.A.R. 1930 – 1936.

- For a fuller analysis, see P.A. Crocker ‘Some Thoughts on The Royal Welch Fusiliers in the Great War’ in Y Ddraig Goch, September 2002, p 135 – 140.

- Later General Sir Alexander John Godley KCB KCMG (1862 – 1957). He commanded the New Zealand Expeditionary Force throughout the war, the New Zealand and Australian Division at Gallipoli, I ANZAC Corps February 1916 – March 1916, II ANZAC Corps until it became XXII Corps in 1917. He was Governor of Gibraltar 1928 – 1932.

- J.F.C. Fuller, Generalship: Its Diseases and Their Cure (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, 1936), p 17.

- Lt-Col C.O. Head “A Glance at Gallipoli”, cited in Fuller, p 11.

- Lomax, Hamilton, Capper, Wing, Thesiger, Broadwood, Feetham, Cape, Lipsett and Ingoville-Williams.

- Barstow, Hopkinson, Mallaby, Lumsden and Tilly.

- John Terraine, The Western Front (London, 1964).

- Dudley Ward, Regimental Records of The Royal Welch Fusiliers, Vol III (London, 1928).

- The great Spanish flu epidemic lasted from 1918 to 1919. Despite its name, it was first detected at Fort Riley, Kansas, U.S.A. on 11 March 1918. It was a truly global epidemic, killing between 50 and 100 million people – probably more than the Black Death and certainly far more, as Wyn Griffith says, than did the war. Its ferocity resulted partly from a high rate of infection – as much as 50%, and partly from the severe symptoms: haemorrhage from the mucous membranes in the nose, stomach and intestine, bleeding from the ears, and massive oedema in the lungs, often resulting in the victim’s death by drowning. Many other victims died from secondary bacterial pneumonia caused by the flu. The death rate was up to 20% of those infected; normally flu has a death rate of around 0.1%. Wyn Griffith was, therefore, lucky to live.

- The Wyn Griffiths had two sons: John Frimston, born in 1919, was killed during a raid on Lubbecke, Germany in 1942; and Hugh Alan, born in 1925, who at the time of writing lives in Florida, U.S.A.