Information Operations

Information Operations - by Lt-Gen Jonathon Riley

RUSI 2007

Information is power, and how one party in any conflict uses that power determines how effective its efforts will be. Information is a force-multiplier, a decision tool, a central part of a campaign: in other words, it is firepower and like many sorts of firepower, it can result in blue on blue if it is not targeted correctly. It can also be a weapon of mass effect.

Current British doctrine defines information operations as:

. . . coordinated actions undertaken to influence an adversary or potential adversary in support of political and military objectives by undermining his will, cohesion and decision-making ability, through affecting his information, information-based processes and systems while protecting one’s own decision-makers and decision-making processes. (1)

US Doctrine is broadly similar, describing information operations as:

. . . the employment of core capabilities of electronic warfare, computer network operations, psychological operations, military deception, and operations security, in concert with specified supporting and related capabilities, to affect or defend information and information systems, and to influence decisionmaking. (2)

There is an immediate problem in these definitions, which are about the application of soft power to influence will or affect decision-making, when we consider some of the other the tools included in the information operations kit, described in same doctrine: operational security (OPSEC), computer network operations, deception, electronic warfare (EW), physical destruction, emerging technology. These are the tools of force-on-force war fighting, or top-end counter insurgency operations. In addition, media operations and civil-military cooperation (CIMIC) are excluded, although they are acknowledged as belonging to the wider information campaign. Moreover, British doctrine goes on immediately to discuss the requirement to focus on the will of adversaries, coalition partners and allies, and the uncommitted. These are very different audiences, who may interpret the same message, or various actions, in different ways, and often we are far from clear about the nature of those audiences and their likely reactions. The very aggressive definition does not, therefore, match with the subtlety implied. Finally, there is no explicit linkage between messages and actions.

Both of these approaches are very much attuned to adversarial conflict, and certainly can be applied to the more intense counter-insurgency campaigns. But they are, to say the least, rather one-dimensional in the context of modern complex emergencies in which insurgency may be only one aspect of the problem of failed states and ungoverned space. In these sorts of emergencies, experience that the combination of terrorists or insurgents and criminals gives great longevity to wars, and can make life much more difficult for western military forces. On the other hand, it can create some marvelous opportunities for information operations to fracture what can be uneasy, mistrustful alliances – but this presupposes that we have the structures to identify and direct the required action. Taken to a logical conclusion, then this indicates that there are times when military and other operations should take place in support of a strategic information campaign. Dealing with malign Iranian influence may be a case in point.

If they are that significant, then information operations in such a context cannot be left solely to a staff branch, no matter whether this is at the tactical, operational, or strategic level: they have to be commanders’ business. Major General Julian Thompson, who commanded 3 Commando Brigade Royal Marines in the Falklands War, suggests that in order to fulfill his responsibilities, any commander must do three essential things:

- Find out what is going on (enemy/own forces/upwards, downwards, sideways/land/sea/air/virtual)

- Communicate his intentions to his subordinates – and, implicitly, to his superiors

- Communicate with the staff so that they can solve problems and maintain situational awareness. (3)

No experienced military commander is likely to argue with that. But because of the operational and information context of modern complex emergencies, I suggest that these three essentials have now become four - the fourth being:

- To explain his actions.

A commander will have to explain his actions to his political masters, to his allies, to his enemies, and to the uncommitted in and beyond the theatre of operations. This tends to drive the remarks made by any deployed commander in a high-profile theatre of operations straight into the strategic arena, because they will be picked up by a savvy media as well as exploited by the enemy, especially an enemy with a better tempo of information operations than we can generate. (4)

This need to explain is highlighted throughout the commander’s principal military business in complex modern emergencies: not activity-led operations like framework security or routine security sector reform; nor sustainment, however challenging; but rather a relatively small number of intelligence-led operations. Some of these will be aimed simply at producing further or better intelligence; others at destroying or capturing particular objectives or people; in a peace support operation they may be aimed at setting conditions for non-military activities, like democratic elections or reconstruction. All will be in some way associated with particular decisive points in the campaign. They do not seek, therefore, simply to gain temporary advantage through violence, but rather to change the situation to advantage. (5) These operations certainly fall into the category of those needing to be explained through information operations, requiring careful coordination of the required effects with the messages given out.

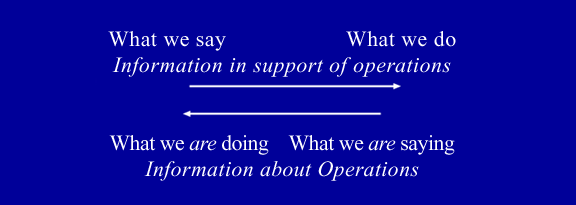

With this in mind, I propose that when talking of information operations in such a complex environment, we are leaving out some words I our current doctrinal description, which if included, might give us a better understanding of what we are doing and why. I suggest we speak therefore of “information about operations”, on the one hand, and “information in support of operations” on the other.

Information in support of operations is probably best handled by the theatre or operational level commander, taking this responsibility away from the man with the tactical problem, and coordinating what is said by whom at the various levels of command. The same applies to control over resources – perhaps more so, since this is really our equivalent of advertising. We often have a good product, but do we advertise it in the way that Mr Toyota advertises his latest car? He gets out there and spreads the message, understanding that the opposition will exploit any reluctance to do so, and punishing him accordingly.

Information about operations, the business of the deployed commander, must be part of his intent and scheme of manouevre. That is, woven into the plan from the beginning and not an afterthought, and within that part of his plan that he writes himself, and with which the staff is forbidden from tampering! It must, too, be resourced properly: intellectually, conceptually, morally and physically.

Why do I make this distinction between information in support of operations, and information about operations? Because there are two processes at work, which are complimentary, yet distinct, and not the same process working in two directions:

First, let us consider information in support of operations, at the strategic and perhaps theatre levels. Here, there has to be a connection between what we say about the purpose of military operations in the greater scheme of things, and what we then do. It is no good, for example, saying this:

Our Purpose in Vietnam is to prevent the success of aggression.

Peace is built brick by brick, mortared by stubborn effort and the total energy and imagination of able and dedicated men. (6)

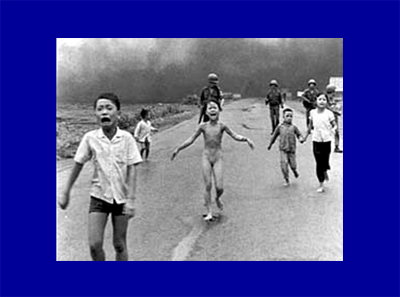

The language of peace, security and reconstruction, if what we then mostly have to do – and what people chiefly see and experience, or outside the theatre of operations they perceive – is images like this:

The British face this same problem in Afghanistan: the mandate for NATO’s deployment is framed in terms of providing security, law and order against violent and terrorist activity, and authorizes NATO forces to take all necessary measures. (7) It should come as no surprise, therefore, that military force is very much in evidence in Afghanistan. However different expectations have been raised in and outside the theatre by comments like these:

Although our mission to Afghanistan is primarily reconstruction, it is a complex and dangerous mission because the terrorists will want to destroy the economy and the legitimate trade and the government that we are helping to build up . . . .Of course, our mission is not counter-terrorism

We would be perfectly happy to leave in three years and without firing one shot because our job is to protect the reconstruction. (8)

Sometimes it is difficult to make this connection between what we say, and what we then do, as in the examples just quoted. If we are very lucky, however, it may be as simple as it was in 1991: the authority for the liberation of Kuwait, for example, called for:

. . . .all necessary means to uphold and implement Resolution 660 (1990) [ie the withdrawal of Iraqi military forces from Kuwait] and all subsequent resolutions to restore international peace and security in the area. (9)

The language was unambiguous, the situation relatively simple, the problem obvious, and the means applied were legal, appropriate and limited to what was required. What we did, was what we said we would do. The messages were consistent and the images positive.

Hard or easy, this is the business of information in support of operations, and it is the business of the theatre commander to make certain that as far as possible, the broad thrust of military activity is in line with the message; that, or change the message.

Another example illustrates this. In the first weeks of 2007 the US government announced its intention to surge a large number of additional troops to Iraq, in order to bring the security situation in and around Baghdad under control. (10) This would create the conditions for effective transition to Iraqi control – part of the required end state of the campaign, but in direct opposition to the advice given to the US government by the Iraq Study Group in its report. At roughly the same time, the British government announced that it planned to reduce troop levels in southern Iraq (11): the result of re-posturing, greater acceptance of responsibility by Iraqi forces, and a much lower level of violence than elsewhere. Both these positions were tenable, but on the face of it, they looked to be in direct contravention, and there was the potential for a series of unhelpful interpretations: the US military and government feeling that its major ally was about to cut and run; other coalition partners perhaps feeling exposed; insurgents using the opportunity to declare that they had driven the British out, or forced a divergence in policy and strategy between the US and British governments; the Iraqi government and people just plain confused; and the British media using this as a stick to beat Blair. This was a perfect example of how and why there needs to be a clear and direct connection between what is said, and what is done, as well as consideration of how to advertise the product. It was the declared intention of the coalition to hand over control progressively to Iraqis, as their capacity allowed: troop reduction would naturally follow.

At the same time, there must be a connection between what we are doing on the ground, and what we are saying about that: this is information about operations, the business of the commander on the ground. This can have a positive side – for example when dealing with military support to humanitarian projects, infrastructure repair, training and education, security sector reform and so on; or describing kinetic military operations when the application of force is legal, necessary, and appropriate. It also has a negative side: that of explaining why the application of force as a tactical effect has been necessary, legal, and appropriate when it may seem to be out of kilter with the broader context of operational or strategic effect. Thus information about operations is inseparable from other aspects of planning and executing operations. An example of how this can work was the raid by 1 Mechanized Brigade on the Office of the Martyr Sadr in Basra in September 2004. The raid itself was led by good intelligence. It was filmed throughout, and immediately afterwards the film was made public. A huge cache of weapons and munitions was shown, in the headquarters of a supposed political party, and moreover in a densely populated area of the city. OMS was wrong-footed and the uncommitted reassured that the raid had been a necessary action using only such force as was required.

Having established why both information in support of operations and information about operations are important; and because of the increasingly strategic nature of information operations both at home and abroad; there are other areas which need to be addressed.

The heart-wrenching picture of the young, naked girl from Vietnam, which was portrayed at the time as an American bombing of Vietnamese civilians, prompts the mention of misinformation – false or inaccurate information (12) – not necessarily part of deception, but resulting from one of several situations. The photograph actually depicted an all-Vietnamese accident, in which the only American participants were the journalists who prepared the report and made this girl famous, and the doctors who saved her life. (13) Misinformation is the old problem that the first report is always wrong; or of partial observation; or of faulty analysis. Devotees of the movie National Lampoon’s Animal House will recall the immortal line by Bluto: “We didn'’t give up when the Germans bombed Pearl Harbor…” The Vietnamese girl highlights the problem of misinformation in the media, sometimes the result of a failure to check simple facts, sometimes the unavoidable product of a confused situation - but it happens across the spectrum of information operations. We must be clear that this is not the same as disinformation – that is, information which is intended to mislead – which can be part of deception. It can also be part of an agenda – political, economic, media – to discredit a particular policy. The faked pictures sold to the Daily Mirror of abuse of Iraqis by soldiers of the Queen’s Lancashire Regiment in 2003, and which led to the demise of the paper’s Editor, are an example. (14)

Perhaps it is time to revise the way that information operations are conducted. We might start with the distinction thrown up by complex emergencies between information as an active function in combat, distinct from intelligence, and other elements of current information operations, which really form part of other functions in combat: EW as part of intelligence; computer network attack as part of firepower; operational security as part of security, and so on. If this distinction is made then matters become clearer straight away. The firewall we erect between information operations and media operations seems to me to make little sense in this multi-media world of ours. If one accepts the idea of connection between words and deeds, it seems to me fundamental that whatever message is being put out by IO and Psyops has to be matched by what is seen in the media. We know that the media gets things wrong – through misinformation or disinformation – nevertheless most people believe what they see in the media and it is therefore vital that any commander does his best to ensure that whatever story is put out to the media and then by the media is true, and therefore credible. The internet too seems to have credibility beyond what it deserves, all the more dangerous because of the speed and quantity of information which it carries. It is essential to get our messages out and dictate the agenda; if we do not it will be dominated by the enemy’s version, or the media’s version. Ask anyone in occupied Europe from 1940 to 1944 about what source of information they believed and they will tell you the BBC. The news was not always good – far from it – but it was the truth. Did the massive deception operation before, during and after D-Day concerning where the Allies would land bother them? I do not think so. Asking that same question about trust today in the Middle East would probably get the answer “Al Jazeera”.

Herein lies the clue to unscrambling one of the objections to merging media and information operations: that we can use disinformation on the enemy but not on our own people. If we separate disinformation – which is really an aspect of deception and therefore aimed at the enemy – from information about or in support of operations, which has to be the truth no matter what the audience, then there really is no difficulty. We should never lie, nor cover up, because we should have no need to do so. If we are ever in that position, we are fighting the wrong war.

We also have to be fast with our messages, as well as credible: tempo matters here. Modern technology means that news gets to TV screens faster than it does through military channels, or current government controlled information outlets. Winston Churchill said that “a lie gets halfway round the world before the truth has got its pants on.” (15) Governments are bureaucracies, and therefore centralised, and therefore slow. States like China, Zimbabwe and North Vietnam may be able to control the media, but in democracies, the days are gone when governments or leadership elites could control information and thereby control populations. Even in the late 1980s, the Warsaw Pact knew to its cost that advances in computer and telecommunications fields had shattered any monopoly of control over information. This process has simply accelerated since.

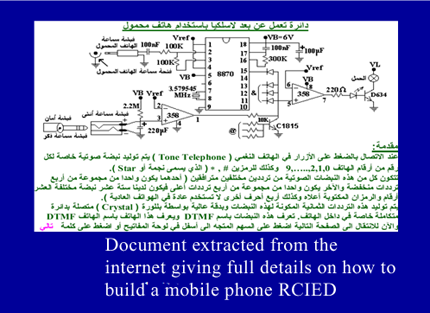

At the same time, the merging of these once separate areas has brought the ability to reach ever larger audiences. The mobile phone is now part of the equipment of any self-respecting insurgent or terrorist, and any insurgent attack can be recorded and broadcast. I have seen images of coalition patrols being ambushed in Iraq, and of Westerners beheaded, on cell-phone screens in the most remote areas, and within a very short time of the event. The horribly mismanaged execution of Saddam Hussein is another case in point. In many parts of the world, cell-phones are commonplace, service providers having jumped straight from hand-delivered mail to cellular networks, without the need to go through the step of fixed telephone communications by cable. Our information operation needs to be able to exploit this, not to have to react to it and its effects.

Of course speed is relative to the media that the target audience uses – back to the business of understanding the target audiences. In many parts of Africa and central Asia, for example, this is not TV or the internet that spread information, it is radio, or sometimes handbills, or even sermons. Part of NATO’s successful information operation in Bosnia during SFOR days rested on a popular, SFOR-run, local radio network based in Banja Luka, plus the free distribution of hand-held, clockwork, radios. Whose face delivers the message is also highly important.

This brings me to question of legality and from that, ROE. ROE relate to the use of soft effects in information operations, media operations and psychological operations as much as to hard effects. They are not law, but are derived from laws, although one might be forgiven for the view that the virtual realm is at present as much ungoverned space as is Somalia! The most likely opponents of western strategy today are not states, but non-state groupings, whose command structure, as far as they can be said to have one, operates in the virtual realm. The internet contains information on, for example, putting together IEDs, becoming a suicide bomber, how to reach Iraq and joint the jihad, and much else besides. And as the Estonians have recently discovered, we are as likely to be attacked in the virtual realm as in the physical. We, I suggest, need to have a ROE profile which matches the enemy’s modus operandi in every sphere of conflict if we are going to conduct information operations whenever and wherever we need to do so.

Finally, we must ask ourselves whether is it possible still to achieve surprise, given that surprise is largely the product of security and deception, and both may include the use of deliberate disinformation, or the withholding of information? The answer has to be yes. Coalition forces, in particular Special Forces, do this every day in anti-terrorist operations in Iraq, and even in Britain. We can, for example, hide information about one operation within a mass of information on other operations: all similar-seeming, and all true. Distinguishing between them is like, as one US Admiral puts it, “trying to pick the spider-shit out of the pepper.” (16) We can control access to organizations, people, information itself. We can act covertly. We can, where necessary, gag. We can distract attention or dislocate our opponents. But we need to be clear when we are doing this, why, and be certain that it is appropriate and legal. There remain cases where because of the needs of security, the public does not have “the right to know.”

SOURCE NOTES

- Joint Doctrine Publication Information Operations (Joint Doctrine and Concepts Centre).

- Joint Publication 3-13 Joint Doctrine for Information Operations.

- Major General Julian Thompson (with Commodore Giles Clapp) The Falklands War, lecture to the Higher Command and Staff Course, Joint Services Command and Staff College, March 2003.

- For example, Richard Norton-Taylor “Afghanistan close to anarchy, warns general” (interview with General David Richards, Commander ISAF) in The Guardian, 21 July 2006.

- Rupert Smith The Utility of Force (London, 2005).

- LB Johnson The Vantage Point: Perspectives of the Presidency, 1963 – 1969 (New York, 1971).

- UNSCR 1707 of 2006.

- Secretary of State for Defence John Reid, BBC News, 2006.

- UN SCR 678 of 1990.

- “Bush sends in more troops”, Daily Telegraph, 11th January 2007; Ros Taylor “The blood of others” in Guardian Unlimited, 11th January 2007.

- See, for example, “Blair refuses to match US troop ‘surge’ in Iraq”, Daily Mail, 8th January 2007.

- As defined by the concise edition of the Oxford English Dictionary.

- Ronald N Timberlake The Fraud Behind the Girl in the Photo (1999).

- “Editor sacked over ‘hoax’ photos”, BBC News 24, 14 May 2004

- Ascribed to Sir Winston Churchill, circumstances unknown.

- Vice-Admiral David Nicholls, DCOM US CENTCOM, 2007.