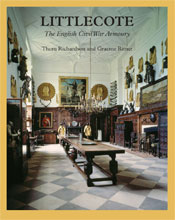

Littlecote: The English Civil War Armoury

Unpublished Contribution to the Littlecote Armoury Catalogue

Lieutenant-General Jonathon Riley CB, DSO, PHD, MA

Foreword to the Catalogue of the Littlecote Armoury

Foreword to the Catalogue of the Littlecote Armoury

This article was submitted to the Royal Armouries by Lieutenant-General Jonathon Riley, but never published.

The greatest 17th Century arsenal of English weapons and equipment is that held by the Royal Armouries, underlining the continuity between the Armouries in its current form and functions and that of the Civil Wars. Now, the heritage side of the Royal Armouries business has become its dominant preoccupation, although it still continues a role in national security through the work of the national firearms centre. In the mid to late 17th Century, national security was the dominant theme as the Armouries led in equipping the national armies for war while heritage, in the form of displays calculated to impress foreign visitors, were an established although subordinate function begun in the time of the Tudors.

However this armed schizophrenia – the veering of the organisational persona between heritage and national security – was not confined to the Armouries, for it existed in many a country house and castle throughout Britain and indeed Europe. In Britain, the Royal castles and Garrisons and then a significant number of private houses – including Alton Towers, Wilton House, Thame Park, Chirk Castle and Apethorpe House – all displayed large collections of arms and armour that had been assembled for warlike use, but retained for reasons of decoration or status. The majority of these lasted into the late nineteenth or early twentieth centuries when they were for the most part broken up for sale. But some survived and the most important of these was that at Littlecote House which had been assembled in the aftermath of the English civil wars by the Popham family. The most distinguished member of the family at that point, Alexander Popham, had commanded a regiment of horse in the cause of Parliament; although by the mid 1650s, with military dictatorship firmly established, Alexander gradually turned his coat to the extent that by the time of the Restoration, which he worked for and supported, he was able to keep his families holdings of land and their position in the counsels of the great..

In point of fact, by the mid 1980s, Littlecote was the only survivor. The House itself had passed out of the hands of the Popham family to that of Wills, but its current owner was the millionaire businessman Peter de Savary. It too looked likely to suffer the fate of most of its comparators by being sold off piecemeal at public auction – indeed Sotheby’s had already printed the catalogue and a sale was scheduled for six weeks’ time. The collection had been well known to many students of arms and armour since at least by the early 19th century, but it had not been studied in detail until the Royal Armouries teams of Thom Richardson and John Paddock [armour and associated material], and David Blackmore and Graeme Rimer [firearms], were permitted access by the then owner, Sir Seton Wills. This study convinced the newly-established Board of the Armouries that this was a resource that had to be saved. Thanks to the concerted efforts by the Royal Armouries and a group of dedicated supporters, the enormous sum of £580,000 was raised within the short six weeks’ period of grace to secure the entire contents of the armoury.

What was it that generated this strength of feeling and sense of urgency? Well for one thing, it was the fact that, as already noted, it was an unique survivor. Secondly, it is again unique as a snapshot of the arms a Parliamentarian officer and landowner would be required to acquire, in order to equip a company of foot – anything up to 100 men – and a troop of horse which might number around fifty men, which he had raised. Only by both raising and equipping these men could he both demonstrate his commitment to the cause and ensure that he would be rewarded with a commission and have the expense of paying and victualling the troops taken on by Parliament. In doing this, he was of course entering a contract with his tenants – or at least the yeomen among them – who would find their own horses and their own subsistence for the period of risk between mobilisation and the picking up of the bill by Parliament. Thirdly, and consequent upon this circumstance, the armoury contains the largest concentration of arms known to have been acquired at one time during the English civil wars. It includes, for example, thirty-six buff coats (buff being a corruption of boeuf, the hide from which the coats were made, rather than a reference to their colour), approximately eighty matchlock muskets arquebuses, sixty horse pistols, helmets for horse and foot, back-and-breast armour, pikemen’s armour and all the ancillary items that one might expect, from holsters and slings, to baldricks, powder flasks and swords. What does not survive in large numbers is as revealing as what does: those things that could be re-cycled into civilian use are noticeably absent: in particular, boots, gauntlets and horse furniture.

Once the collection had been secured, detailed study could be undertaken and this has revealed previously forgotten details of the form, construction and nature of a variety of period military equipment. These include English-made armours for both horse and foot; the late matchlocks; the emerging importance of the flintlock in pistols and carbines; and perhaps most notably of all, the buff coat, of which so many survived at Littlecote. For the contextual historian, as well as the arms and armour specialist, the Littlecote armoury proves in some specific areas what was thought to be the case from written or pictorial accounts of the English civil wars: for example, in contemporary European warfare, the bulk of the cavalry was still heavily protected, encased in three-quarter armour with a close helmet and relying principally on the pistol to break up formations of enemy pikes before closing with the sword for the final act. In England, only one regiment was equipped this way in the whole of the armies of parliament. Instead, troops and regiments of horse were dressed in the manner of dragoons, or harquebusiers as they were generally known, dragoons being essentially mounted infantry as much as cavalry. And although the armies of Parliament again included only one formally designated regiment of dragoons, that of Colonel Okey, the inference of the Littlecote armoury seems to be that troops of horse were equipped as multi-purpose units. They had to be prepared to fight on foot, to deliver fire from the saddle, or to produce the shock of a charge with the sword. Going back to the contract with the tenants, it was the more educated, more religiously and politically aware of the yeomanry who would have filled the ranks of such troops of horse. The landless labourers would have been mustered into the foot, whose equipment in the form of musket, pike, morillon helmet, back and breast armour and tassets is just as well represented as is that of the horse. Taken as a whole, the final lesson we should draw is that although in some cases this mass of equipment might be produced by local blacksmiths, leather workers, saddlers, or farriers there is far, far more that could only be produced by specialists: gun-makers, armourers and powder-makers. The outlay of money involved would have made a huge dent in the annual income of a family like the Pophams – and thereby, demonstrated exactly where their loyalties lay.

The publication of the catalogue of the Popham family armoury of Littlecote has been a cherished ambition of the Royal Armouries ever since the acquisition of the collection in 1984. Advances in scholarship and advances in the technologies of analysis, photography and printing mean that we can make a virtue of the delay – for today we can produce a volume whose standard of presentation is worthy of its subject, a volume to rank with the Henry VIII catalogue and the Carlo Paggiorino volumes on the armouries of von Trapp, Wallace and the Royal Armouries. We should therefore salute Thom Richardson, Graeme Rimer, John Paddock and David Blackmore, along with all those other members of the Royal Armouries academic and curatorial faculty who have contributed to this work and in particular... Together, they have made that ambition a reality.

Copyright © 2010 Jonathon Riley

The Littlecote Catalogue

Littlecote: The English Civil War Armoury was written by the Royal Armouries’ Thom Richardson and Graeme Rimer and published in September 2012 to coincide with the Leeds English Civil Wars conference.

The publication forms the catalogue raisonné of the Popham Armoury, secured for the nation by the Royal Armouries over 25 years ago, and is a major contributor to our understanding of 17th century arms and armour in England